This post (first in 6 months – it’s been a busy year!) is the result of the end of the first year of our 2nd three year research project we are carrying out in line with the Princes Teaching Institute. Our first project 2014-17 was on the use of cinema in French, German and Spanish (film clips and short films). Our current project focus is “The development and use of authentic wider cultural resources” primarily aimed at KS3 and 4. This year’s focus was using literature pre-A Level in Years 7-11. We also presented it at a recent Staff meeting, as one of the school’s priorities for 2018-19 was department research projects.

The rationale for our project chimes with two authentic literary extracts appearing in the new specification GCSE Reading papers. Exposure to literature is now no longer the domaine of A Level only. We have sought to produce similar resources to those in the GCSE papers (+ extended activities) to get students used to this from a young age, as well as giving them a deeper appreciation of target language cultures. We have been using some extracts in French years prior to the 2016 GCSE specifications containing literature. Extracts from Guène, Begag, Joffo and Sagan has been developed for KS4 with success i.e. students found them feasible and motivating.

Until very recently, there has bizarrely been no pedagogical research on this that I or others know of, as it is so new to MFL GCSE teaching. Fortunately however, Fotini Diamantidaki, PGCE tutor at UCL Institute of Education has just published a book on the subject called Teaching Literature in Modern Foreign Languages (Bloomsbury Academic), which should prove useful to any colleagues wanting some ideas. We will certainly be purchasing a department copy. Some teachers I have spoken to think there is a strong case for avoiding literature pre-A Level as it is too difficult, texts are edited, and there is no research to back up its use. However, we would disagree, and I find the ‘for A Level only’ rather an old fashioned view. Literature and culture are widely studied in Classics from the early staging of learning, as well as all the grammar, so why not in Modern Foreign Languages? There is a way of breaking texts down to exploit them for maximum output, to complement and vary our teaching input, teaching students how to avoid the pitfalls of having to understand every word or idea. Our resources comprise an extract with questions in English and sometimes in the TL for older students, as well as allowing us to review/highlight verbs and tenses, cognates, deeper language analysis, answering Qs, gap-fill, translation, biographical background of the author, hearing the extract on youtube etc. We can stretch our students very well and get a great deal of good value out of a short text. They can also produce some wonderful presentation display work, for example writing original poems inspired by simple Prévert poems, or writing their own war poem in November.

In French we have used some children’s literature: T’choupi and Peppa Pig for Yr7, and for Years 8-11, A level text extracts and poetry, as well as classic and popular modern literature such as Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, a Maupassant short story, Bonjour Tristesse, Victor Hugo and Rimbaud war poems, and an extract from a Montaigne essay. Modern literature is also be used such as Chanson douce by Leila Slimani or No et moi by de Vigan.

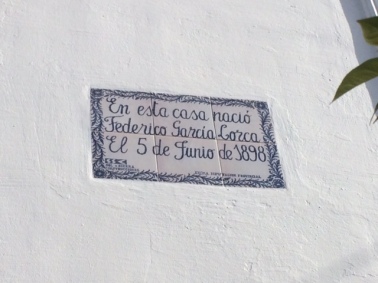

In Spanish, we have some Harry Potter, authors Baroja, Galdós, and Lorca poetry and prose, and some more Harry Potter, which students always enjoy.

In German, we have some Heine poetry (for KS5) and East German literature.

Comic books (particularly French BD) are also a possibility, but we are yet to exploit these. (see below for examples of some of the above)

Our students respond very well to these extracts. A survey of a Year 10 group conducted in May 2019, found that 90% cited ‘real culture’ and ‘fun’ as reasons they enjoyed authentic literature. All strongly agreed or agreed that reading increases enjoyment in lessons and 61% strongly agreed that it inspires them to read the book in full or read more in TL. 83% prefer literature to songs. They also love the fact these texts are studied at A Level & beyond – it inspires them and, I believe, with other authentic culture we use, leads to good retention beyond GCSE with decent sized groups in three languages.

We will continue producing these resources and incorporating them into SoWs. Looking to next year, our 2nd year of the PTI project focus will be exploiting art, music or history/society/heritage (again a direct link to A Level and to be confirmed). The noticeable output in terms of language understanding, encouraging risk-taking, not stressing over full meaning, and reading for gist is invaluable; it also prepares students for (the thought of) A Level study, as well as taking them beyond the confines of any syllabus or unit of work. We have also found that they find the actual GCSE tasks relatively straightforward as a result. However, far more important is the cultural capital aspect of exposure to literature.

We as teachers have at times been reading new texts and developing imaginative ways of making them accessible, which could open up new texts for us to study with our A Level students. It is, and should be, aspirational for staff and students alike. Developing these resources makes preparation and teaching more enjoyable, invigorates our curriculum, and adds to our love of subject, which can surely only be a good thing!

Paul Haywood, Head of Modern Foreign Languages, July 2019

____________________________________________________________________

Three examples that have worked well

Read the extract from Harry Potter y la Piedra Filosofal, by J. K. Rowling (Year 10)

El señor y la señora Dursley, que vivían en el número 4 de Privet Drive, estaban orgullosos de decir que eran muy normales, afortunadamente. Eran las últimas personas que se esperaría encontrar relacionadas con algo extraño o misterioso, porque no estaban para tales tonterías.

El señor Dursley era el director de una empresa llamada Grunnings, que fabricaba taladros. Era un hombre corpulento y rollizo, casi sin cuello, aunque con un bigote inmenso. La señora Dursley era delgada, rubia y tenía un cuello casi el doble de largo de lo habitual, lo que le resultaba muy útil, ya que pasaba la mayor parte del tiempo estirándolo por encima de la valla de los jardines para espiar a sus vecinos. Los Dursley tenían un hijo pequeño llamado Dudley, y para ellos no había un niño mejor que él.

Los Dursley tenían todo lo que querían, pero también tenían un secreto, y su mayor temor era que lo descubriesen: no habrían soportado que se supiera lo de los Potter.

Answer the questions in English

- The Dursley family would describe themselves as:

- What is Mr. Dursley’s job?

- How is Mr. Dursley described? (3)

- What does Mrs. Dursley spend a lot of time doing?

- Who is Dudley?

- What do the Dursleys have?

____________________________________

Chanson douce (2016) de Leila Slimani (Year 9)

« Ce matin, ils ont fait le marché en famille, tous les quatre. Mila sur les épaules de Paul, et Adam endormi dans la poussette. Ils ont acheté des fleurs et maintenant ils rangent l’appartement……ils rassemblent les livres et les magazines qui traînent sur le sol, sous leur lit et jusque dans la salle de bains……ils plient les vetements des petits…..Ils nettoient, jettent. Ils voudraient qu’elles (les nounous) voient qu’ils sont les gens bien, des gens sérieux et ordonnés qui tentent d’offrir à leurs enfants ce qu’il y a de meilleur. Qu’elles comprennent qu’ils sont les patrons.»

- The action takes place: a) in the afternoon c) in the morning b) at Christmas

- There are five members of the family. True/False

- The little girl, Mila, is: a) on her mother’s knee b) on her father’s shoulders c) in a pram d) holding her brother’s hand

- Where did they go that day, and what did they buy? (2)

- What did they do in their apartment?

- Give three details of what exactly they did to make this successful? (3)

- Some things were on the floor, others went as far as which room?

- They wanted potential nannies to see that (choose four correct answers):

- They are good people

- They are happy

- That they are the in charge (the bosses)

- They pay well

- They are serious

- They want to give their children the best

- They are wealthy

- They have a spacious apartment (4)

_______________________________________________

No et moi (2007) de Delphine de Vigan (Year 9 or 10)

Our teenage protagonist, Lou (the moi of the story) is remembering when she was little and how she thought her ears used to stick out!

Quand j’étais petite je passais des heures devant la glace à essayer de recoller mes oreilles. Je me trouvais moche, je me demandais si ça pouvait se réparer, par exemple en les enfermant tous les jours dans un bonnet de bain, été comme hiver, ou dans un casque de vélo, ma mère m’avait expliqué que bébé, je dormais sur le côté, l’oreille mal pliée. Quand j’étais petite je voulais être un feu rouge au plus grand carrefour(…….) pour protéger les gens. Quand j’étais petite je regardais ma mère se maquiller devant le miroir, je suivais ces gestes un à un, le crayon noir(…….), le rouge sur les lèvres, je respirais son parfum, je ne savais pas que c’était si fragile, je ne savais pas que les choses peuvent s’arrêter, comme ça…..

(p.44, Editions Jean-Claude Lattès)

- Surlignez tous les verbes à l’imparfait dans une couleur (imperfect verbs)

- Surlignez les mots que tu connais dans dans une deuxième couleur (words you know)

- Surlignez les mots transparents dans une troisième couleur (cognates)

- Which SIX things did she used to do when she was little or a baby? Put a cross next to them. She used to…..

| play the violin | not eat carrots |

| spend hours in front of the mirror | sleep on her side |

| watch her mother | want to be near a red fire |

| go to the cinema | breathe in her mother’s smell |

| know that things can change | think she was not pretty |

- Traduisez le texte

As it’s the half term holiday, I have the time and energy to write a post I meant to write seven weeks ago.

As it’s the half term holiday, I have the time and energy to write a post I meant to write seven weeks ago.